Screenshot of an Excel worksheet demonstrating use of formulas" width="1024" height="435" />

Screenshot of an Excel worksheet demonstrating use of formulas" width="1024" height="435" />If you are like most Canadians, your employer pays you biweekly. Assume you earn $12.00 per hour. How do you calculate your pay cheque every pay period? Your earnings are calculated in $ as follows:

12.00 × (hours worked during the biweekly pay period)

The quantity “hours worked during the biweekly pay period” is the unknown variable. Recall that the word variable simply represents a quantity that can vary in value. Notice that the expression above appears lengthy when you write out the explanation for the variable. Algebra uses symbols to make such expressions more convenient to manipulate. To shorten the expression, making it easier to read, we can assign a letter or a group of letters to represent the variable. In this case, you might choose [latex]h[/latex] to represent “hours worked during the biweekly pay period.” This rewrites the above expression as follows:

[latex]12.00 \times h[/latex] or simply [latex]12h[/latex]

Unfortunately, the word algebra makes many people worry. But remember that algebra is just a set of tools that can help in solving a numerical problem. It is used to demonstrate how the pieces of a puzzle fit together to arrive at a solution.

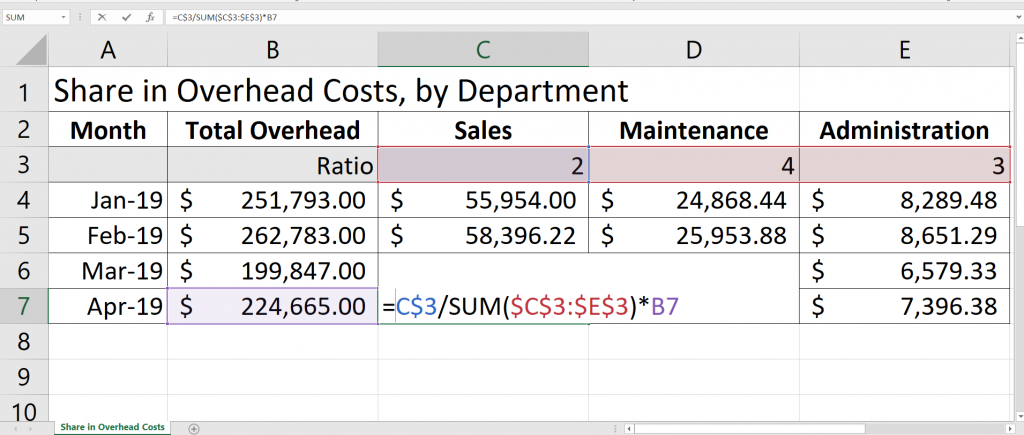

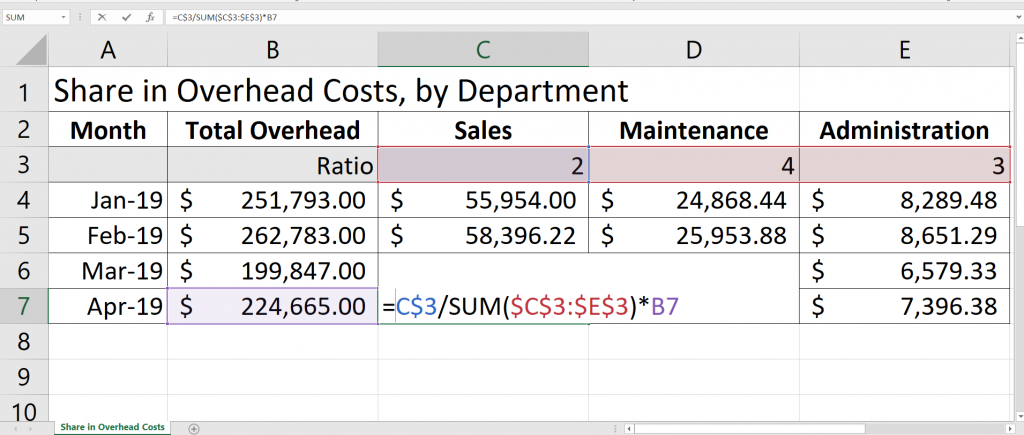

For example, you have used your algebraic skills if you have ever programmed a formula into Microsoft Excel. You told Excel there was a relationship between cells in your spreadsheet. Perhaps your calculation required cell C3 to be divided by the sum of cells C3, D3 and E3, and then multiplied by cell B7. This is an algebraic expression. Excel then took your algebraic expression and calculated the solution by automatically substituting in the appropriate values from the referenced cells (your variables). See the example below:

Screenshot of an Excel worksheet demonstrating use of formulas" width="1024" height="435" />

Screenshot of an Excel worksheet demonstrating use of formulas" width="1024" height="435" />

Algebra involves integrating many interrelated concepts. In this textbook we will discuss the concepts that are important to business mathematics. Your understanding of algebra will become more complete as more concepts are covered over the course of this book.

This section reviews the language of algebra, including exponent rules, basic operation rules, and substitution. In Section 1.2 you will put these concepts to work in solving one linear equation for one unknown variable along with two linear equations with two unknown variables. Finally, in Section 1.3 you will explore the concepts of logarithms and natural logarithms.

Understanding the rules of algebra requires familiarity with four key definitions.

A mathematical algebraic expression indicates the relationship between the specific values represented by numbers or variables and the mathematical operations that must be conducted on these values. For example, if [latex]h[/latex] represents the number of hours worked and the hourly wage is [latex]\$12[/latex], the expression [latex]12h[/latex] calculates the total amount of dollars earned for [latex]h[/latex] hours worked. Note that, even though by convention we don’t write a multiplication symbol in this expression, [latex]12h[/latex] represents [latex]12\cdot h[/latex]. Specifically, [latex]12[/latex] must be multiplied by the value of [latex]h[/latex].

Note also that an expression does not include an equal sign, or “[latex]=[/latex]“. An expression only tells you what to do and requires that you substitute a value in for the unknown variable(s) to solve. There is no one definable solution to the expression – an expression can represent many different values, potentially infinitely many. The value of the expression will change as the value of the variables in the expression change. An algebraic expression is not the same thing as an algebraic equation, however an algebraic equation is built from algebraic expressions.

An algebraic equation is a statement that says two algebraic expressions are equal. This equation can often, but not always, be solved to find a solution for the unknown variables.

Examine the following illustration to see how algebraic expressions and algebraic equations are interrelated.

Consider two algebraic expressions:

[latex]6x+3y[/latex] and [latex]4x+3[/latex]

Each of these expressions represents a value that can be calculated if we were given values for [latex]x[/latex] and [latex]y[/latex].

we are imposing a condition on these two expressions, stating that they must produce equal values. This in turn imposes a condition on the values of [latex]x[/latex] and [latex]y[/latex]; we can potentially no longer substitute any value for [latex]x[/latex] and [latex]y[/latex] because we may end up with a statement that is not true.

Can you determine whether a particular value or a set of values is a solution to a given equation? Try it out:

In any algebraic expression, terms are the components that are separated by addition and subtraction. In looking at the example above, the expression [latex]6x + 3y[/latex] is composed of two terms. These terms are [latex]6x[/latex] and [latex]3y[/latex]. A nomial refers to how many terms appear in an algebraic expression. If an algebraic expression contains only one term, like [latex]12h[/latex], it is called a monomial (mono = one). If the expression contains two terms or more, such as [latex]6x + 3y[/latex], it is called a polynomial (poly = many).

Terms may consist of one or more factors that are separated by multiplication or division signs. For example, [latex]6x[/latex] consists of two factors. These factors are [latex]6[/latex] and [latex]x[/latex]; they are joined by multiplication to create [latex]6x[/latex].

In practice, the term most commonly used is simply coefficient and it represents the numerical coefficient in the term.

Here is an example: Suppose we have an equation of the form

Each side of the equation is an expression composed of different terms, which are in turn composed of different factors, and the two sides are connected by the equal sign, making this a statement of equality, i.e., an equation.

The left side is a sum of two terms: [latex]\frac[/latex] and [latex]4xy^2[/latex].

The term [latex]\frac[/latex] can be rewritten as [latex]\fracx[/latex] and is therefore composed of two factors: [latex]\frac[/latex] and [latex]x[/latex]. In this form of the term, [latex]\frac[/latex] is the coefficient of [latex]x[/latex].

On the right side we have the difference of two terms: [latex]x^3[/latex] and [latex]2y[/latex].

The term [latex]x^3[/latex] can be thought of as a single factor, it can be thought of as composed of the three factors [latex]x[/latex], [latex]x[/latex] and [latex]x[/latex] or as composed of [latex]1\cdot x^3[/latex]. The latter is very useful when algebraic rules require you to consider the (numerical) coefficient of the term. If no numerical coefficient is stated, it is implied to be 1.

The second term in this difference is [latex]2y[/latex] and it is composed of the coefficient [latex]2[/latex] and the variable [latex]y[/latex].

We could also look at the expression on the right side as a sum of two terms: [latex]x^3+(-2y)[/latex]

In this case, the coefficient of the term [latex]-2y[/latex] is [latex]-2[/latex].

Indeed, this can get very confusing. But with practice you can get very familiar with the language of algebra and thus be able to use it to solve complex problems.

Check your understanding of the terms equivalent expressions, coefficients and factors through this series of multiple choice exercises:

Exponents are widely used in business mathematics and are integral to mathematics of finance. For example, when applying compounding interest rates to any investment or loan, you must use exponents. Also, if a particular quantity changes sequentially by a specific percentage, you must use exponents.

The basic meaning of exponent is a mathematical shorthand notation that indicates how many times a quantity is multiplied by itself. However, this can be expanded to a more general concept involving exponents.

When [latex]n[/latex] is a natural number ([latex]1, 2, 3, \ldots[/latex]) and [latex]b[/latex] is an arbitrary number, we use the symbols [latex]b^n[/latex] to represent

We say that [latex]b[/latex] is raised to the exponent [latex]n[/latex].

The format of an exponent is illustrated below:

Assume you have [latex]2^3 = 8[/latex]. The exponent of 3 says to take the base of 2 multiplied by itself three times, or [latex]2 × 2 × 2[/latex]. The power is 8. The proper way to state this expression is “8 is the power of 2 to the exponent of 3.”

Many rules apply to the simplification of powers, as shown in the table below.

| Operation | Rule | Explanation |

| 1. Multiplying powers with the same base | [latex]y^ay^b = y^[/latex] | When multiplying powers with the same base, copy the original base and raise it to the sum of the original exponents. |

| 2. Dividing powers with the same base | [latex]\dfrac = y^[/latex] | When dividing powers with the same base, copy the original base and raise it to the difference of the original exponents. |

| 3. Power of a power | [latex](x^a)^b = x^[/latex] | When a power is raised to an exponent, copy the base of the original power and raise it to the product of the original exponents. |

| 4. Power of a product | [latex](xy)^a=x^ay^a[/latex] | When raising a product to an exponent, multiply the original factors, each raised to the original exponent. |

| 5. Power of a quotient | [latex]\left(\dfrac\right)^a=\dfrac[/latex] | When raising a quotient to an exponent, divide the original numerator and denominator, each raised to the original exponent. |

| 6. Zero exponents | [latex]y^0 = 1[/latex] | By definition, any nonzero base raised to exponent 0 is equal to 1. (Note that [latex]0^0[/latex] is undefined.) |

| 7. Negative exponents | [latex]y^ = \frac[/latex] | By definition, a base raised to a negative exponent is 1 divided by the original power but with the positive exponent. |

| 8. Fractional exponents | [latex]y^>= \sqrt[b][/latex] | A fractional exponent is a different way of writing a root. When a power has an exponent that is a fraction, the denominator of the original exponent represents the root of the base raised to the numerator of the original exponent. |

Recall that mathematicians do not normally write the number [latex]1[/latex] when it is multiplied by another factor because it doesn’t change the result. The same applies to exponents. If the exponent is a [latex]1[/latex], it is generally not written because any number multiplied by itself only once is the same number. For example, the number [latex]2[/latex] could be written as [latex]2^1[/latex], but the power is still [latex]2[/latex]. Or take the case of [latex](yz)^a[/latex]. This could be written as [latex](y^1z^1)^a[/latex], which when simplified becomes [latex](y^z^)[/latex] or [latex]y^az^a[/latex]. Thus, even if you don’t see an exponent written, you know that the value of the exponent is [latex]1[/latex].

Simplify the following expressions:

| a. [latex]h^3h^6[/latex] | b. [latex]\dfrac[/latex] | c. [latex]\left[\dfrac\right]^3[/latex] | d. [latex]1.49268^0[/latex] | e. [latex]\dfrac[/latex] | f. [latex]6^[/latex] |

Answers:

(multiplication of powers with the same base)

(division of powers with the same base; negative exponent definition)

(power of a quotient, power of a product; power of a power)

(definition of zero exponent)

(factoring of fractions, dividing powers with the same base)

(definition of fractional exponents)

Check through these exercises if you can state the laws of the exponents and apply them.

Simplifying unnecessarily long or complex algebraic expressions is always preferable to increase understanding and reduce the chances of error.

For example, assume you are a production manager looking to order bolts for a product that you make. Your company makes three products, all in equal quantity. Product A requires seven bolts, Product B requires four bolts, and Product C requires fourteen bolts. If [latex]q[/latex] represents the quantity of products required, you need to order [latex]7q + 4q + 14q[/latex] bolts. This expression requires four calculations to solve every time (each term needs to be multiplied by [latex]q[/latex] and you then need to add everything together). With the algebra rules that follow, you can simplify this expression to [latex]25q[/latex]. This requires only one calculation to solve. So what are the rules in general?

In math, monomials with the same variable components (i.e., same literal coefficients) are called like terms. When it comes to addition and subtraction of monomials, only like terms may be added or subtracted.

Monomials with like terms are added and/or subtracted by adding or subtracting their coefficients, as indicated by the addition or subtraction operation.

From the previous example, you require [latex]7q + 4q + 14q[/latex] bolts. Notice that there are three monomial terms, each of which has the same variable component, [latex]q[/latex]. Therefore, you can perform the required addition by adding the three coefficients:

[latex]7q + 4q + 14q=(7+4+14)q=25q[/latex]

A common mistake in addition and subtraction is combining terms that do not have the same variable component. You need to remember that the variable components must be identical. For example, [latex]7q[/latex] and [latex]4q[/latex] have the identical variable component, which is [latex]q[/latex]. However, [latex]7q[/latex] and [latex]4q^2[/latex] have different variable components, [latex]q[/latex] and [latex]q^2[/latex], and therefore cannot be added or subtracted (but they can be multiplied or divided, using exponent laws).

Remember that if you come across a variable component with no coefficient in front of it, that coefficient is assumed to be a [latex]1[/latex]. For example, [latex]x[/latex] has no written coefficient, but it is the same as [latex]1x[/latex]. Another example would be [latex]\frac[/latex], which is the same as [latex]\frac>[/latex] or [latex]\fracx[/latex].

On a similar note, mathematicians also don’t write out variable components that have variables with exponent of zero. For example, [latex]7x^0[/latex] is just [latex]7(1)[/latex] or [latex]7[/latex]. Thus, the variable component is always there; however, it the variable has an exponent of zero. Remembering this will help you later when you multiply and divide in algebra.

Examine the following algebraic expressions and indicate how many terms can be combined through addition and subtraction. No calculations are necessary. Simplify as much as possible.

Simplify the following algebraic expressions.